The Money - Slim Rose

Times Square Records

1961 - 1965

Slim Rose

Times Square Records - Acappella - 1997 - Wayne Stierle

Wayne was one of the creators of Acapella. It all happened as follows: Along with Donn Fileti, Wayne discovered unreleased master recordings that were to be purchased on behalf of three people, that included Donn, Wayne, and industry vet Leo Rogers. When Leo backed out of the deal, it was taken to "Slim" at Times Records, who made the purchase. Donn left the area, and Wayne continued on, eventually owning a few of the masters from the huge tape and demo findings. These tapes included practice tapes by the great Connecticut group, The Nutmegs. Like many practice tapes, these recordings were done without paying a band, as simple showcases for either the song, or for an arranger to listen to and thereby write an arrangement for a band or small combo.

These recordings were done without music, and not planned for release whatsoever. Prompted by Wayne, "Slim" decided to release The Nutmegs recordings, although he had offered to give them to Wayne in return for his various work with Times Records. ("Slim" was not very impressed with The Nutmegs, and Wayne taught him the historical value of the group that had been so important in 1955 with "Story Untold").

"Slim" felt the recordings that had no musical background needed to be highlighted as such, in part to make sure they weren't returned by customers, and in part to show the difference they represented compared to "normal" vocal group recordings. They spent weeks kicking the ideas around, with Wayne voting for various names such as "Subway Sounds", and others.

Finally "Slim", who wanted to press the records, opened a dictionary and found a' capella, the "high class" term used for operatic type music done without background. It was decided that if this was what it was going to be, then it would be changed to a word that didn't even exist: Acapella. And so, the word and the style was born, and the label company was called with the copy for the first releases. This was the beginning of "Acapella", and the start of this word meaning "rock n' roll or r&b vocal groups". (As Wayne likes to point out, the first releases were put in the Italian section of many record stores, who assumed they were foreign records.). ".....we started something that we didn't intend to start....and I still think the name is wrong........but it's way too late to do anything about it..........".

Times Square Records - Vol. 1 - 1994 - by Donn Fileti

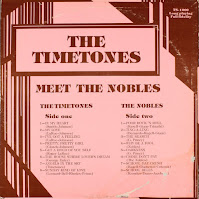

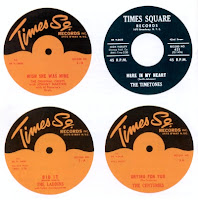

Times Square Records was the first label truly devoted to doo-wop. With fifty odd singles released between 1961 and 1964, Times Square spearheaded the R&B group harmony revival of the early sixties and directly inspired the Relic, Lost Nite, and Candlelite labels also specializing in doo-wop reissues. The first two releases on Times Square were "(Here) In My Heart" by the Timetones and the Summits' "Go Back Where You Came From," two original songs issued in 1961 which were far superior to many records actually produced in the fifties.

The story of the Times Square label is linked with that of the Times Square Record Shop, that legendary purveyor of oldies located in the heart of Times Square, Broadway and 42nd Street. Under the wise ownership of Irving "Slim" Rose, the subway arcade shop influenced radio play and record sales nationwide in the early sixties. To comprehend the Times Square label and its colorful origins, let's go back to the fall of '59.

As word quickly spread and more and more eager listeners hungry for group harmony sounds tuned into Fredericks and became regular customers at the Times Square Shop, Rose was faced with dwindling supplies and mounting demand for hard-to-find and out-of-print 45s (albums were just not "collectible" in the early sixties). Aided by Jerry Greene, who, (according to his account) persuaded Slim to stop selling costume jewelry and concentrate on records instead, Rose managed to have various group harmony 45s repressed in small quantities, often for his store's exclusive use, at least for a short period.

Since the doo-wop sound was still current in New York City in the early sixties, it was possible for some 45s specifically reissued at Slim's behest to receive much wider airplay as new singles since they were not national hits (or, in many cases, even known) on first release. For example, four of Slim's young employees bought the master of the Capris'"There's a Moon Out Tonight" for $200 from the defunct Planet label. The Shells' "Baby Oh Baby," the Chanters' "No, No, No," and, notably, the Edsels' doo‑wop classic, "Rama Lama Ding Dong, all began their long ascent of the national charts from that lowly subway arcade.

Billboard ran a prominent feature story about the Times Square concept; record producers and execs from local labels followed the kids down the stairs to Slim's shop. There was a distinctive "Slim" sound; usually a passionate, high-pitched lead voice (Slim loved the Frankie Lymon knockoffs), plenty of falsetto and high tenor parts, and, of course, the ubiquitous rumbling bass. The classic R&B sound of the pioneer groups of the early fifties - the Orioles, Five Keys, or Ravens - was perhaps too complex (and maybe too black) for the mostly white teens who crowded Slim's store. A few discerning collectors (Mr. D'Elia, for one) recognized the merits of the Swallows and Dominoes in the early sixties, but most customers opted for the kiddie lead -- The Elchords"' Peppermint Stick," the gimmicky doo-wop, the Five Discs'"I Remember," orthe ringing ballad - the Admirations' "The Bells of Rosa Rita," all prime examples of the "Slim sound."

The Times Square label was born in the winter of 1961. Slim had acquired the rights to several masters and wanted to manufacture repressings on the original labels. Clarence "Jack Rags" Johnson, the co‑writer of "Desirie" by the Charts and ownerof the tiny Cee-Jay label, approached Slim with an exceptional new mixed group (three blacks, two whites) which, of course, they christened (by way of a contest) the Timetones. Slim was initially opposed to the creation of his own label; he was very busy just running his shop. Wayne Stierle, who helped in the store and supplied Times with key reissues, persuaded Slim that his image would be greatly enhancedby a custom record label. According to Stierle, he then fabricated the first simple black and-silver design for the Times Square label, used only for "(Here) In My Heart" and "Go Back Where You Came From." Slim soon dropped Stierle's design for a more elaborate black-and-orange logo, obviously copied from the legendary Chance Records of Chicago label art.

The Five Sharks were a young white group from Long Island who were known as the "Florals" when they recorded their version of "Stormy Weather." To capitalize on his self-created "Stormy Weather" promotion (he kept offering more cash each week for an original 45 of the Five Sharps' 952 Jubiliee recording, "Stormy Weather;" he never had to pay up and, to this date, no 45 has ever turned up), Slim renamed the Florals the "Five Sharks" and pressed up his first 100 copies on a unique multicolor vinyl Times Square pressing with a longer intro creating an instant collector's item.

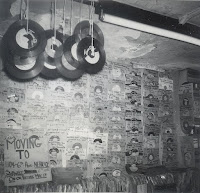

On May 1, 1963, Times Square Records moved one long block east to another seedy subway arcade location, Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street. The new store had much additional space, but still retail sales lagged. Slim continued to release weaker singles on Times Square, championing the group harmony cause a few months before the advent of the British Invasion. The Decoys' "It's Going To Be All Right" (TS#8) was the best of his new singles. Produced by Al Browne, it was a custom "oldie" with a fresh, exciting sound. Perhaps Connie Questell and her male backup group from the Melrose section of the Bronx were a few years too late; they were a vibrant new group who, unfortunately, were tagged as an "oldies" act. They appeared at the Village Gate, the Baby Grand in Brooklyn, and Palisades Park in New Jersey.

Relic Records (then Relic Rack, Inc.) bought the Times Square Record Shop and all masters on March 15,1965. Relic reissued most Times Square singles in the late 1970s and unissued sides on LPs in the eighties. Eddie Gries and I would not be in this business today were it not for Times Square Records. The preservation of R&B vocal groups harmony owes a huge debt to Irving "Slim" Rose's Times Square Records. - Donn Fileti - October, 1994

Times Square Records - Vol. 2 - 1999 - by Donn Fileti

Irving "Slim" Rose's Times Square Record Shop occupied just a few hundred closely‑packed square feet in the Times Square subway arcades in the early 1960s. Yet Slim's influence extended far beyond the narrow boundaries of his crowded shop; during the peak years of Times Square Records (1960‑62), Slim and his teenage prot6ges were responsible for a significant number of charted hits, most of which were reissued because of demand initially generated by Slim's customers.

When such records as the Capris' "There's a Moon Out Tonight," the Edsels' "Rama Lama Ding Dong," and the Shells' "Baby Oh Baby" hit the Top 100 on Billboard and Cashbox charts, Slim decided to launch his own label, Times Square Records, solely devoted to newly recorded and vintage R&B group harmony. In 1961 this often meant issuing masters only a few years old, as there were legions of great group records piled in distributor basements, which received little attention the first time around. By cleverly inflating the prices on these out‑of‑print gems (this was the very first rock 'n roll collectors' venue), Slim, under the tutelage of Brooklyn teens, Jerry Greene and Jared Weinstein, among others, created a burgeoning demand for otherwise forgotten R&B platters. They created the mythology of the "group" as almost a sacred entity; if a recording did not feature a rock'n roll or R&B lead, bass, and harmonizing vocals, it didn't matter. They conveniently relegated blues and rockabilly, not to mention Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Fats Domino and the great R&B single artists of the early fifties—Amos Milburn, Charles Brown, Wynonie Harris, even Joe Turner- to the ten cent bins.

Since many original R&B pressings were on colored vinyl-red, purple, or orange were the cheaper grades and cost a penny or so less than the standard black), young collectors prized their 45s on "colored wax." Since there was little difficulty obtaining various colored biscuits to press 45s in the early sixties, Slim opted for color pressings on most of his initial Times Square single releases. He thus made them more attractive to the young collectors who flocked to his store from all over the city and surrounding areas. By refusing to sell wholesale to other dealers, at least for a time, Rose kept valuable "exclusives" to lure customers to his seedy Times Square locations.

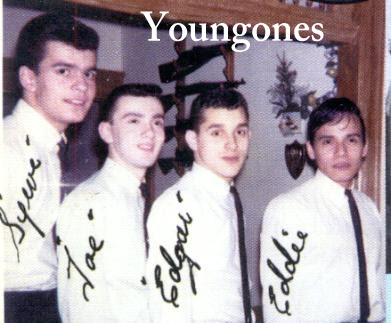

The Times Square label was a musical hodge-podge of R&B group harmony, ranging from great groups like the Crests, Nutmegs, Five Satins, and Timetones, to well‑intentioned amateur practitioners of the art (the El Sierros and Lytations, for example). Times Square Records was launched in the winter of 1961 with the Timetones' local noisemaker, "Here In My Heart," followed by Nicky and the Nobles' "Poor Rock'n Roll" (originally on Klik), Johnny Maestro and the Crests' "No One to Love" / 'Wish She Was Mine" (first on Brooklyn's tiny Joyce label), and the Five Satins' virtuouso acappella rendering of "All Mine," among other rather distinguished recordings, and ended rather sadly in 1964 with a multitude of forgettable demo and acappella sides by interchangeable local groups. If industry pros like Atlantic's Jerry Wexler subtly mocked the so called "Golden Age of Acappella" (his words), it was because of the off-key and poorly recorded singles, which appealed to many young group harmony fans in the early sixties. Perhaps for the teenage listener, the Youngones, Lytations, or El Sierros had mastered certain vocal tricks, which had heretofore eluded their older mentors, the Cardinals, Clovers, or Drifters. Even Slim's own Moonglows group is of dubious authenticity circa 1964.

It was Slim's (or perhaps that of one of his underpaid employees) genius to label as acappella mere demonstration or rehearsal recordings, which were often voiced to showcase new songs, or as preparation for the real session, which would always have instrumental accompaniment. He leased a treasure trove of reasonably fashioned demos and finished masters from Tom Sokira and Marty Kugell's Klik and Standard labels in New Haven, Connecticut, which embodied, among many others, some particularly fine performances by Fred Parris and the Five Satins and Leroy Griffin's Nutmegs. The latter group's "Down in Mexico," "Let Me Tell You," and "Wide Hoop Skirts" set an almost impossible standard of excellence for amateur groups to follow. The difference was obvious to any discerning listener: the Nutmegs were a professional group with a national chart history ("Story Untold" "Ship of Love"), sporting an incredible bass and one of the most unique lead voices in the annals of R&B group harmony. Most of the acappella groups, which proliferated in the mid‑sixties and later could, only try to emulate their immensely talented predecessors.

Although Slim's vision once momentarily embraced a national chain of small oldies shops all bearing the Times Square logo (he needed a smart franchise, rather than the useless sycophants who sometimes surrounded him), he additionally made several poor business decisions which contributed to the impending demise of the entire Times Square Records operation. Slim was initially only concerned with obtaining a steady supply of "exclusive" product for his shop alone, so the focus of the label included acquiring out-of-print masters to reissue. If you could locate even a couple hundred copies each of the Nobletones, "Who Cares About Love," the Paragons, "So You Will Know" or Lonnie and the Crisis" 'Bells in the Chapel" in 1962, it would have been cheaper and more cost effective to just sell those original pressings for a buck or two apiece and not bother with new stampers, labels, etc. However, many good original 45s had been completely scrapped or had otherwise disappeared by the early sixties, so there was a definite market for reissues. Slim was also fond of confounding collectors by pairing a better side by a known group with a grade- B" side by another. (the Nutmegs' "Down to Earth," for example, was coupled with the Admirations’ throwaway, "Coo Coo Cuddle Coo.") As long as he pressed a limited quantity on blue, green, or yellow vinyl, there would always be a loyal coterie, however small, of Times Square devotees eager to plunk down their dollars on his messy counters.

After hitting the bottom of the national charts with the Timetones' "Here in My Heart" in 1961, Slim leased their next side, "Pretty Pretty Girl," to Atlantic's Atco subsidiary. Despite more concentrated national push, the Timetones fared better on Times Square than on Atco. When Slim's A&R man and partner on the label, Clarence Johnson, suddenly died, Slim turned almost exclusively to reissues. The Timetones' third outing, "House Where Lovers Dream," was issued several years later in 1964 when the magic was really fading. Too bad this very talented and popular New York City group didn't get to record more original songs.

Times Square Records became the prototype for several important early 45 collector reissue labels in the sixties. Slim's defectors, Jerry Greene and Jared Weinstein, relocated to Philadelphia, where they quickly developed their Lost Nite Records which had been initially launched from Times Square. Wayne Stierle's Candleite Records and Eddie Gries's Relic logo put New Jersey on the 45 oldies reissue map. The songs on this compilation (and its companion volume, "Golden Doo Wops of Times Square Records: Vol. 1 - Relic CD 7091) reflect directly the taste of Irving "Slim" Rose, the sole proprietor of Times Square Records until it was sold in 1965, and that of his young customers, who became today's R&B group harmony collectors. - Donn Fileti - August, 1999

MY MEMORIES OF TIMES SQUARE RECORD SHOP

by Jerry Greene

My memories of Times Square Records go back 35 years, to when I was 15 years old. In those days, I listened to Alan Freed on the radio during the week and heard many great songs by different vocal groups. That began my infatuation with vocal groups and R&B records - when I heard a song I liked , I had to have the record.

On Saturdays, my friend Marty Dorfman and I would go up to Manhattan looking for any records by singing groups that we didn't already have. We bought used records for 5 & 10 cents a piece, paying up to 25 cents for hard-to-finds we really wanted. At those prices, I was able to amass a fairly large collection.

One of the best stores Marty and I came across was a little store off the corner of 43rd Street & 6th Avenue. It was a costume jewelry store that also sold records at twenty for a dollar. I guess I must have visited that store six or seven times and got most of the records in my collection there. The store's name escapes me now, but I do remember that it was owned by a couple named Slim and Arlene. As winter approached in late '58, our trips to the store had to stop because of the weather and our responsibilities as high-school students.

In April or May of 1959, we went back to the store and found it was no longer there. On our way back from the record stores on 42nd & 8th Avenue, we entered the subway at the foot of the Times Building at 42nd & 7th. As we walked down the first flight of stairs to the landing, I glanced into the store near the entrance and saw the gentleman who had owned the store on 43rd Street, Slim.

I remember walking into the store & meeting Slim at the doorway. I noticed he didn't carry records any more; his new place was strictly a costume jewelry store. I asked him what had happened to the records from the other store. He told me he had them all stored in boxes at the back of this new store. He said he didn't think he wanted to sell the records here, since this new store was fairly small, and selling costume jewelry was much more profitable. I asked him if it would be all right for me to go through the boxes of records in the back room; maybe I would find some records I could buy from him. Out of five or six thousand records that I looked through, I picked out maybe three to four hundred that interested me. I only had about two or three dollars with me at the time, so I asked Slim if he would hold the records I couldn't pay for and I would come back in the following Saturdays to pick them up, and he agreed. I asked if he thought about putting the records out in the store again and if he would be getting any more new records in. He said he really didn't know.

I asked Slim if he would be interested in letting me work in the store after school every Friday, and on Saturdays and Sundays so I could pay for the records I had picked out. He said he really wasn't doing enough business to be able to afford any help; it was just him and his wife. Besides, he didn't feel there was any need for another worker in the store. I suggested that maybe if he brought the records out from the back, I could run the "Record Department" for him. Slim laughed and told me that with the amount of money he had been taking in on the records in the other store, he couldn't even afford to buy lunch.

Then I suggested to Slim that he wouldn't even have to pay me in cash, he could pay me in records. I thought it could become a very profitable business. The records he had were very desirable and he probably could do a lot better than a nickel a record. He didn't really understand what I was getting at, and I showed him that if we took the sleeve of the record and wrote on it the artist, title, the release date, and put 250 or 500 or $1 or whatever on the sleeve, we could take in more money than just the 50. Because of the larger profit, it would make a lot of sense for him to hire me. He really wasn't getting what I was saying; he couldn't comprehend that someone might actually want to pay more than a nickel a piece for these records. I said, "Let's try it for a week and see what happens. You don't have to pay me unless you take in more than the nickel a record you were getting before."

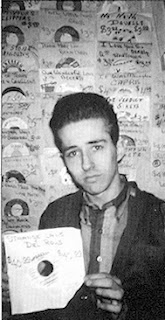

I wrote up the info on the sleeves of maybe 50-75 records and took push pins and put them along the back wall of the store, the wall facing the customers as they walked in. With a Magic Marker, I wrote the word "Records" on a piece of paper and stuck it in the window. The following Friday after school I came back and asked Slim if he had sold any records for more than the nickel he used to charge. He said he figured he had taken in about $23, and maybe $21 of that was more profit than he had made at his old selling price. Since my idea seemed to be successful, he agreed to let me work in the store and I got paid 75cents an hour, with the equivalent in records being 15 45's per hour. He only let me work 5 hours, until we could generate more business. Needless to say, the whole back wall was written up and I tried to do as much business as I could, so I could make this a regular part-time job on the weekends. The following week, the Record Department took in around $40, and from that point on, I HAD A JOB!

I'd been working part time at Slim's store for maybe three months. In that time, the business never really did more than $100 per weekend with the oldies, but Slim was very happy with that, and so was I. But I also felt there was tremendous potential in what we were doing, if we could make people aware of it. After all, we were in a sort of remote location, with not much traffic walking by the store.

On Saturday nights I used to listen to an oldies show on WHOM called "Night Train With Alan Fredericks". I felt that if we took out a couple of spots on the Night Train show, we could bring in a lot more business. One Saturday right before closing, at about 11:30, 1 went over to the radio station where Alan Fredericks was broadcasting and waited for him to get off the air. I remember bringing about 5 or 6 records with me I felt would fit right in, and that I hadn't ever heard on the Night Train show. Being that the show was only an hour every week, I got to know the music and remember the records he played, because they all happened to be records I liked.

I introduced myself to Alan as he came out of the radio station. I said I was a listener of his and I worked at a record store that sold exclusively the kind of music he played. I told him the store had a lot of records that fit in with the show, and I was wondering if he could play some of them and perhaps in turn promote the store. Alan said that he didn't feel he could do something like that, because the mentions would be commercials, and since radio stations make their money on commercials, they wouldn't go along with his promoting something without getting paid. I believe he said spots at that time in the evening were $10-15 each and I should check with my boss and see if he was interested in taking out maybe 2 or 3 spots on the show promoting the store, and he'd be glad to do the commercials. I told Alan I'd have to talk to Slim the next day (Sunday) and get back to him, stopping by the station the following Saturday. When I told him about Alan's suggestion, Slim looked at me like I was crazy and said there was no way he would spend $15 on a spot to promote the store. He said there were so many record stores, it didn't make sense to do anything like that.

The following Saturday, I went back and explained the situation to Alan, giving him some more records to play. I then suggested to Alan that perhaps while he was playing some of these records, he could once or twice mention that they were "lent to him by Jerry who works at Times Square Records at 42nd and Broadway." In doing that, maybe we'd get a response and I could eventually convince Slim to advertise on a regular basis, if it proved to be successful.

I remember some of the records I had given him that week: "Tormented" by The Heartbeats, "Dream Of A Lifetime" by The Flamingos, and one of my favorites, "Without A Friend", by The Strangers. Also included was a record by The Five Crowns, either "A Star" or "You're My Inspiration" (I'm not sure which side he played). Alan was familiar with The Flamingos and The Heartbeats, but he didn't know these sides of theirs. He'd never heard of either The Strangers or The Five Crowns. At the time, Alan was playing what you would call more "mainstream" records, by groups that were more familiar, like The Heartbeats, The Valentines, and The Cleftones, groups that were known by a lot of collectors. What I tried to do was give Alan alternative music, things that weren't heard all the time, which would give the show more interest. Alan said he was getting a lot of phone calls asking for different records, and he would give me mentions during the show in exchange for lending him the records. That week, Alan mentioned the store twice during Saturday night's show.

The Sunday hours at Slim's store were 12:00 to 9:00. The Sunday after our first mention on the Night Train show, I got off the subway at about 11:30. As I headed towards the store, I couldn't help noticing a crowd of people. I walked through the concourse and got out on the other side of 7th Avenue, because there weren't any people on that side. I crossed the street and tried to make my way through this huge crowd to the subway entrance where the record store was. I asked some of the people, mainly kids, what was going on. They said they were waiting for the record store to open. I pushed my way through the crowd of kids and after about 5 or 10 minutes, I got close to the steps where the store was and waited for Slim to show up.

By 12:00, Slim still hadn't arrived. My usual routine on a Sunday after opening was to go across the street to Grant's and buy Slim two hot dogs and a soda, so I thought I should check to see it he was at Grant's. Sure enough, Slim was sitting at the counter. After I told Slim the reason for the crowd outside, we ventured back across the street and opened the store, and were busy till closing. It was so exciting to see that many people interested in the kind of music I liked; I felt we were on the right track with the advertising.

A lot of the customers who came in those early days objected to the prices. They didn't like the idea that we were selling some of the records for more than $1. 1 told them that if they had a copy of say, "Secret Love" by The Moonglows, which we were selling for $3, 1 would be glad to give them $1.50 in credit towards anything they wanted. Basically, at that point, I began to offer anybody half in credit for anything that they brought in that we had on the wall at a higher price. The records we offered at a higher price were those I felt were harder to get, and didn't see that often. I had been to 10-15 different shops as a collector, and I could tell hard‑to‑find records from the more common ones by their availability.

Realizing that they could maybe make money on this inspired people to get rid of the records they didn't care for and exchange them for other records. I would go through people's collections and pull out records they wanted to trade in and give them half of what we had them on the wall for. If they were records that we normally sold for $1, I'd give 500 credit toward any other purchase. If there were records I didn't know by major groups, I'd also give 500. If they were records that didn't look like records we would sell, I would figure them at somewhere around 50 each.

We made out very well with that trade in system, because in many cases we would pay 50 for a record and end up selling it for $1, making 20 times the initial investment. The records that we were paying half a dollar for, I'd listen to at night. If I thought they were good, I'd sell them for $2, $3, or $5. By the end of the summer of '59, when I had to go back to school, the most we'd sold a record for was $10, and I remember Slim was thrilled to make that much of a prof it. Since our inventory was growing so quickly, Slim and I came in early on one Sunday and built counters along the left and right walls. We expanded the counters, making the store 100% records. The costume jewelry was moved to the boxes in the back room. Because of the trade‑in system, our inventory grew quite a bit. We sold the records at the back counter and along on the radiator opposite the counter for 3 for a dollar (we couldn't watch those that much, so if we lost them it wouldn't be that big a deal). We put the 78s all the way in the back of the store. We did very little in 78s, but because they were group records and the kind of music we were selling, and occasionally we did get some people asking for 78s, we took them in on trade. The most we paid on a 78 was, I think, 250, and if it were a group record, we would pay 50. If they were anything else, we weren't interested in them, but people ended up leaving them there anyway.

Around September of '59, 1 had to go back to school. Up till then, it had just been the three of us at the store: Slim, his wife Arlene, and myself. I then suggested to Slim and he agreed that someone else would have to be there during the day, so I hired one of the customers I liked and used to go to lunch with, Harold Ginsberg. Until that time, I had been the only one giving credit for records, since Slim wasn't really that knowledgeable about oldies then. So I taught Harold what to do; I showed him how much credit to give on the trade‑ins, and how to be fair with the customers.

School started up again in September, and I was attending The School of Visual Arts at 23rd Street in Manhattan. School let out at about 2:00, and I would get to the store around 2:30. Every Friday, as soon as I got to the store, Slim and I would go straight to Portem Distributors on 1 Oth Ave., where Slim got all his old 45s back then. We paid, I believe, about 20 per record. We always took a big Checker Cab back from Portem, giving the driver an extra $5 so we could bring back 40 or 50 cartons of records.

Also on Fridays, I would pick out about 15 records for Alan Fredericks to feature on the weekly Night Train show. I used to write notes about each of the records, maybe who the lead singer was, or if this was the artist's second or third record, or what label the record was on, and any other pertinent information. I would leave the store at around 9:00 on Fridays and go over to 53rd and 1st Avenue, where Alan lived at Sutton Terrace. I left the records with the doorman. We did this for about a year; Alan would get the records, play them that Saturday night, and when I brought new records on Friday night, I'd pick up the old ones.

Occasionally, I'd call Alan and ask what he thought of the records, what were the most requested records, and if there was anything special he wanted. Alan was a very easy person to deal with. I'd call different record companies and ask them to reissue certain titles and when we got them in, Alan would say that "Times Square Records now has available for the first time on the Atlas label 'I Belong To You' by The Fi-Tones, and 'Yvonne' by The Parakeets." If there was anything we had just gotten in that week, Alan would announce that as part of our spot. If records received a lot of requests, or people were looking for hard-to-find records, he'd sometimes play them and offer $5, $10, or $15 or $20 or whatever it might be for the record in credit towards other records.

I recall that once on a trip to Philadelphia I picked up a record by The Hideaways called "Can't Help Lovin' That Girl Of Mine". I had never heard it before and thought it was a great record. I remember programming the record on the show and offering $5 in credit. Maybe two weeks later I offered $10. 1 think the record went up to $100 in credit towards another purchase, but we weren't able to get another copy.

A lot of records got their values from that show, because of their availablity or their scarcity. A lot of records were started on the show through offering credit. If the demand became great, we would try to contact the companies and have them reissue them. The first record that we re-issued was "Sweetest One" by The Crests on the Joyce label, for which we received hundreds of calls. I contacted the record company and we ordered 3,000 copies of the record. In the first two weeks, we sold close to 1,000 of them.

Night Train had a very loyal audience. As time went on, the show's popularity grew and our sales in the store increased steadily and things were going along very well. Occasionally, though, we had a few problems. A lot of times collectors would come in or congregate outside the store and deal and trade records among themselves. Then they began to approach customers who were on their way into the store, asking to see what records they were bringing in to sell or trade for credit. I was forced at times to ban some collectors from coming into the store because of their soliciting other collectors outside. This didn't make me too popular at the time, but I felt a responsiblity to Slim and I took it upon myself to do these things, since I felt part of the business and a lot of its success were due to my efforts.

Probably the most interesting part of my job at Times Square Records was tracking down different manufacturers and getting them to reissue different product on their labels. I enjoyed dealing with the various people at these companies. I remember going to Hull Records and meeting Bea Kaslin and persuading her to reissue some of the Hull titles for which we received requests. I bought her overstock on all the old records by The Heartbeats, The Avons, The Belftones, The Legends and The Desires. There was a new record out at the time by The Desires, and it was always interesting to get new titles.

I met and dealt with George Goldner of Rama and Gee Records, Hy Weiss of Old Town Records, Ben Smith of Atlas Records, Bobby Robinson of Red Robin Records, Paul Winley of Winley Records, Sid Nathan of King Records, and Herman Lubinsky of Savoy Records. There were also people from a lot of the smaller labels, like Gil Snapper at Worthy Records (The Interiors), and Bob Schwade at Music Makers Records (The Imaginations), Hiram Johnson at Johnson Records (The Dubs, The Shells) and Jack Brown at Fortune Records.

In retrospect, maybe contacting Jack Brown wasn't such a good idea. I had made a deal with him to get "The Wind" by The Diablos reissued, along with 8-10 other Diablos records, plus maybe 10‑15 other records on the Fortune label that we had gotten reissued, This led to an unfortunate situation. In my discussions with Jack, he mentioned that he had a warehouse in Detroit with about 50,000 records. Slim's wife Arlene, whose mother lived in Detroit, offered to take a trip to Fortune Records. She could go through the records and let me know what was there, and pay her mother a visit as well. I bought Arlene a round-trip ticket at the Greyhound bus terminal.

Soon after arriving in Detroit, Arlene called me to say she wasn't coming back and she wanted me to tell Slim! I told her I didn't think it was my place to tell my boss that his wife was leaving him. So, Arlene told Slim herself, and she didn't come back. Arlene and Slim had a little boy, Bobby, who Slim raised on his own. Slim was depressed for several months about what had happened and sort of withdrew from the business. He would come in late and didn't seem to care very much about what went on at the store.

When Slim came around, about 2 or 3 months later, he went completely the other way. He tried to control what the people heard, forcing his musical preferences on the customers. He concentrated on playing more uptempo songs, like "Silly Dilly" by The Pentagons.

Some of these records did well, like the flip side of "Ankle Bracelet", "Hot Dog Dooly Wah" by The Pyramids, which was one of Slim's favorite records and became fairly popular. All the Charters records and things like that were very popular. But there were certain ones that were a little off-the-wall, that a lot of people didn't like. One of the people that didn't like this new direction was Alan Fredericks. In the summer of '60, Alan objected to playing a lot of these records, and it caused a lot of friction between Times Square Records and the Night Train show. Slim, in trying to be more active, took over the programming of the show and began alienating Alan. I believe they stopped speaking to each other altogether.

I left the store in November of 1961, when I moved to Philadelphia to open a record store that was the same kind as Times Square Records. I felt that I couldn't open a store in New York and go into competition against Slim, because in spite of everything, I still felt very close to him.

There are a few reasons for my leaving Times Square Records. When I was starting my second year of college, in September of 1961, 1 had asked Slim if there was a chance of my getting a raise. I had been making the same 75cents an hour since I started more than two years earlier, but instead of getting paid in records for the last year, I had been receiving money. The cost of art supplies was quite high, and I really needed the cash. Slim told me that it if I quit art school, he would give me $1 an hour. He wouldn't compromise; if I didn't quit school, I wouldn't get the raise. After all I had done for the store and my loyalty to Slim, his giving me such an ultimatum really hurt.

The deciding factor in my leaving Times Square Records came about on the day Slim came in to the store, handed me a $2995 bill for a 1960 or - 61 Plymouth Fury, and asked me to make out a check. (It was part of my job to pay all the bills and balance the checkbook each month.) Opening the checkbook, I said, "I thought you didn't have a driver's license." He said he was going to learn to drive, Jenny was going to teach him. Jenny was a girl Slim had hired to work in the store on a part-time basis. Slim became infatuated with Jenny, but I don't think she felt the same way about him. Slim got to the point where he would do anything to win her over, and so now he was buying her a car! I felt very slighted; Slim had refused to give me a raise without any reason, but he was spending $3000 to buy a car for Jenny. Looking back now, the picture seems very clear, but back then I had trouble dealing with it; this was probably the main reason for my leaving Times Square Records.

When I left, there were five people working at the store: Slim, Jenny, Harold Ginsberg, Johnny Esposito (another friend I made at the store and ended up hiring), and another gentleman Slim had worked with years before in a different business who came back to work with him again. I had been attending The School of Visual Arts 5 days a week till 2:00 in the afternoon and The Fashion Institute three nights a week, but when I quit my job at the store, I quit school as well and moved to Philadelphia.

The Record Museum, my first store, opened in Philadelphia on the day after Thanksgiving in 1961.

-------- The End --------

Sources:

http://lulusko.www7.50megs.com/ - (website was last updated in 2000)

(Courtesy of Wayne Stierle Val ...)

Undated letter from Wayne Stierle outlining his role in the creation of the Times Square label.

Jerry Greene: Liner Notes to "Memories of Times Square Record Shop, Vol. 1-5" (Collectables CD #5172-5176).

Reminiscing with Eddie Gries about the finer details of the Times Square label that have been overlooked or forgotten

Comments from this blog

ira blacker has left a new comment - Slim did not rename the Five Sharks from the Florals as he never knew the name nor met the group prior to releasing the record if ever. I found the group as the Florals and produced the record, named the group The Five Sharks and sold the record to Slim. :-)

Comments from this blog

ira blacker has left a new comment - Slim did not rename the Five Sharks from the Florals as he never knew the name nor met the group prior to releasing the record if ever. I found the group as the Florals and produced the record, named the group The Five Sharks and sold the record to Slim. :-)

Comments

Post a Comment